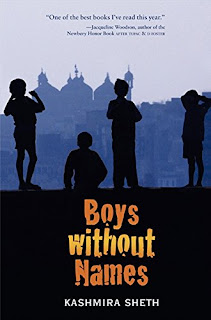

'Boys without Names' by Kashmira Sheth

Boys without Names, published in 2010, is the remarkable story of the young protagonist, Gopal, as he works in a Mumbai sweatshop. Driven by poverty, Gopal’s family move to Mumbai with the hope of starting a better life. However, Mumbai proves to be challenging, and financial desperation results in Gopal’s venture for employment in the city. Unfortunately, Gopal is tricked and taken away from his family to work in a small and stuffy sweatshop alongside five other boys. The boys are forbidden to talk to each other and survive on little food under the threat of their violent boss, Scar. Day by day, the children repeat the long working hours with no access to the outside world. It is only when Gopal encourages the children to unite through storytelling that the children stand a chance at planning their escape. Interestingly, the theme of the novella simultaneously reflects contemporary issues of sweatshop labour. The workers oppression can only be overturned once the discussion of labourers rights is discussed, as Gopal questions: ‘Who are the lucky people who will buy them? Maybe one will end up in a young girl’s room. She will never know a young boy like her made this frame with his sweat and tears while his heart ached for his family’.

Although Boys without Names is not a true story, it is based on the true experiences of many individuals that Sheth researched during her stay in India. Through her research, Sheth discovered: ‘child labor will persist as long as there is widespread poverty and children must work to feed themselves and their family, and as long as there is a market for cheap goods’. Fast fashion and disposable culture prospers on the availability of low production costs. Likewise, Western greed is accounted for by the poverty of the Eastern workers. Sheth’s characters are representations of the real victims of global capitalism.

One thing that I particularly liked about the novel is the role of storytelling that explores the children’s experiences leading up until the sweatshop – not all of the children have homes to return to, or even alternative options. One of the most common comebacks I personally receive when discussing the cruelty of sweatshop labour with people, is: ‘well, they wouldn’t have anything if we didn’t buy from the companies’ – a response that I have always found ignorant, but nevertheless a debatable statement. Sheth explores the logistics around sweatshop labour and challenges this particular opinion. Most importantly, she grants a voice to the subaltern – the bodies that are quashed by the importance of profit - those without names.

As the locked room symbolises, the children are trapped in an exploitive system that is hidden from the consumer’s eyes. In a globalised market whereby origin is hidden, Sheth exposes the undesirable reality. Although the children are treated like animals, the children’s young spirits lighten the tone of the novella. Gopal’s hope and the blossoming friendship of the group create an enjoyable read despite the dark undertones. Furthermore, the first person narrative of Gopal offers an innocent perception of an upsetting situation that makes it a suitable read for young readers. I believe that everyone should read this book – a very good read!

Call on companies to disclose information about their factories by signing the petition below:

https://www.hrw.org/GoTransparent #GoTransparent

Comments

Post a Comment